Tomorrow will be my last day of employment for the University of Sheffield, and the first for the University of Bologna.

One of the many blessing of this strange job of mine is that over the years I met a lot of people, and with many of them I developed a fairly close relationship. Seven years ago, when I announced that after over 20 years I would have left the Rizzoli Institute in Bologna to take a chair of biomechanics at the University of Sheffield, quite a few wrote me asking why. Most of them were familiar with the pleasant life that Bologna can offer, and the only Sheffield they knew was that of The Full Monty. Eventually the answer to that question became clear: I moved to Sheffield to make true the dream of a lifetime, the creation of a very large research institute entirely dedicated to in silico medicine.

And Sheffield delivered: the dream came true, and it is called Insigneo. Also, Sheffield turned out to be much better then I thought. When I left for good a few weeks ago, I did it with strong emotions, as this city welcomed me with open arms, I found a lot of friends, and I enjoyed there some of the most exciting years of my life.

So tonight as I change my status on LinkedIn, I am sure I will start to get many emails asking why I am leaving Sheffield and Insigneo. But this time I have my Blog, so here is the explanation, before you ask it. The answer is made of three parts: Brexit, Cycles, Roots.

Brexit

There is not much to explain here I guess. The reasons that attracted so many of us from other European countries to UK are all at risk of disappearing on April 1st, 2018. I came to UK because it was one of the most inclusive countries with an amazing level of multiculturality in the universities, second only to the USA. I came because it was a country with solid economy, with a sensible government, and with a special commitment toward research and the future in general. And, most important, I came because UK was part of Europe, and everywhere in Europe is home. If not for a miracle, on April 1st UK will wake up wrapped in its "little England" xenophobic nostalgia, little island not part of Europe anymore, ready to face a severe economic crisis doubled by a severe political crisis. I was not given the opportunity to vote for the referendum, but I can express my total disagreement with this decision of the people of the UK by leaving the country.

Cycles

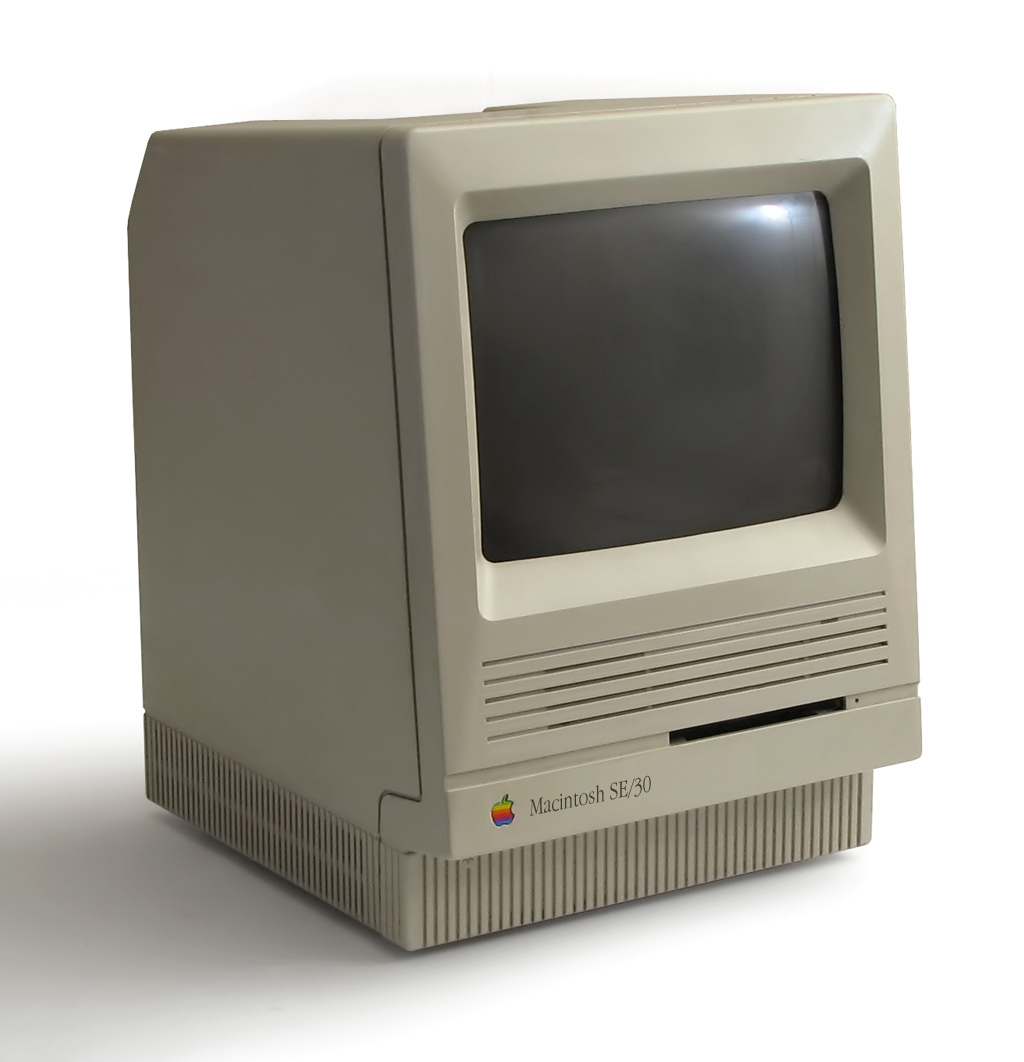

To be honest during most of my career I experienced a lot of professional frustration; while this for sure added fire that drove me to some extents, it also gave me a gastric ulcera. The experience as Director of the Insigneo institute was amazing, and for the first time a couple of years ago I stopped by professionally frustrated. Insigneo was everything I wanted and more, and I was happy, and satisfied. So satisfied that I started to ask myself if this was what I wanted to do until a retired, in ten more years or so. I looked back, and God knows how many jobs I had: I was an engineer in industry, a programmer, a laboratory rat, an entrepreneur, a consultant, a research manager. But the happiest of all jobs for me is to be an academic. You teach, supervise a few master and PhD theses, do research by leading a small group of post-docs. That is what I want to do until a retire. Building Insigneo was a trip, but my cycle is over, now it is time for someone else who has something to prove. "Stay foolish, stay hungry" said Steve Jobs; the cycle is over, I am not hungry anymore, time to move on.

Roots

In these seven years I spent a lot of time with other emigrants, many from my own country. But there is a big difference between them and me: most of them moved to UK in their 20s, early 30s. My wife and I moved in UK when we were 50. We had a very good life in Sheffield, but our roots back home are deep, and they have been calling us back with louder voices as we get older.

-------------

But of course nothing of this would have mattered if I did not received this fantastic offer from the University of Bologna. From tomorrow morning I will be Professore Ordinario (Full professor) of biomechanics in the department of industrial engineering; I will also go back to lead the Medical Technology Lab at the Rizzoli institute, where most of my research career took place.

Many old acquaintances I meet in these days ask me: "are you happy?". My answer is always "of course!". But the truth is that I am happy and I am sad. This change is what I wanted and needed to some extents, but I will miss Sheffield, Insigneo and all my friends and colleagues. I might even come to miss fish & chips, in time!

%2C_from_Los_Caprichos_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)